B.O.A.S

Brachycephalic Obstructive

Airway Syndrome

(BOAS)

What does brachycephalic mean?

Brachy means shortened and cephalic means head. Therefore, brachycephalic dogs have skull bones that are shortened in length, giving the face and nose a pushed in appearance.

What is Brachycephalic Obstructive Airway Syndrome (BOAS)?

The term “Brachycephalic Obstructive Airway Syndrome” (BOAS) refers to a group of conditions resulting from the body conformation of dogs with short noses. Common breeds of brachycephalic dogs include English and French bulldogs, Boxers, Lhasa Apsos, Pugs, Shih-Tzus, Pekingese, Griffin Bruxellois, Bull Mastiffs. Other breeds with longer noses, such as Cavalier King Charles Spaniels and Staffordshire Bull Terriers, can also be affected, although less commonly.

Why are only certain breeds affected by

Brachycephalic Syndrome?

Breeds with short noses have a compacted skeleton, causing a number of malformations, including in their nasal cavities and spine and their tails, but have normal amounts of skin and soft tissue. Their soft tissue is therefore excessive for their skeleton, explaining the amount of skin folds brachycephalic dogs have on their faces and bodies. Similar folds and excessive soft tissues are present inside the body, leading to a number of obstructions, including in

The list of the abnormalities and conditions most commonly seen in brachycephalic dogs, can be explained by this. Because their skeleton is short and small, their nares are compacted on their skull and are consequently closed (“stenotic” nares). Similarly, their nasal cavities are compacted in a small and short nose, making them very tight, which increases the resistance to airflow through them. The end of their palate, called “soft palate” is too long and thick for their flat face. This makes it obstruct the back of their throat, leading at best to loud “snoring” noises when they breathe, at worse to complete respiratory obstruction. Their tongue is too big for their shortened head and obstructs the mouth and throat even more.

Brachycephalic dogs compensate their malformations by “pulling” harder when they breathe in, which creates strong negative pressures in their throat, neck and chest, which in turn can eventually cause secondary respiratory and digestive diseases. This is one of the reasons why brachycephalic dogs frequently regurgitate or vomit. Nearly all dogs suffering from airway obstruction secondary to BOAS have esophageal or gastric lesions on endoscopy, whether they show digestive clinical signs or not.

How can I tell if my dog suffers from

Brachycephalic Syndrome?

All brachycephalic dogs suffer from BOAS to some degree. Some are more affected than others. The less affected ones can often live their entire life without showing much distress, at the cost of constant excessive efforts to open their throat and breathe. The more affected ones will show various degrees of respiratory distress or digestive troubles, ranging from being occasionally short of breath to collapsing on the moderate exercise.

BOAS impacts on all aspects of a brachycephalic dog’s life. Their sleep, for instance, is frequently of poor quality, similar to sleep apnea in humans: dogs tend to choke when they fall into sleep, which wakes them up until they snooze again and so on. Many brachycephalic dogs are consequently chronically sleep-deprived.

Typically, a brachycephalic dog suffering from BOAS shows a combination of signs such as loud breathing and snoring, intolerance to exercise or heat, collapse, gagging, regurgitation and vomiting. Importantly, what is frequently perceived as being normal “for the breed” is already physiologically abnormal. Having difficulty and making a very strong noise breathing may be widespread among brachycephalic dogs, it does not make it normal or without negative health consequences for that!

If your dog is brachycephalic, you should seek a professional opinion to determine whether he or she would benefit from being treated for BOAS.

How is Brachycephalic Syndrome diagnosed?

The diagnosis of BOAS is primarily clinical, This is based on the combination of the signs observed at home, the type of sounds the dog makes when breathing and the physical examination.

Further diagnostics may be required to assess separately the different components of BOAS. Examination of the throat under general anesthesia is most commonly used to assess the soft palate, pharynx and larynx. A CT scan of the head can be used to study the conformation of the skull, with a particular interest in the nasal cavities and soft palate. Nasal cavities are occasionally evaluated by endoscopy (“rhinoscopy”). Lastly, x-rays or CT scan of the chest and abdomen can be required to investigate the presence of concurrent and secondary diseases such as aspiration pneumonia or hiatal hernia.

Other conditions also seen in breeds suffering from BOAS are vertebral deformities over the spine, which can cause compression of the spinal cord, leading to weakness in the back limbs, or even paralysis. Deformed (“cork-screw”) tails can also cause discomfort, either by poking into the perineum or by causing chronic skin fold disease.

How is Brachycephalic Syndrome treated?

As most of the problems included in BOAS result from upper airway obstruction, the main initial focus is unblocking the airways. This is most commonly achieved by surgically widening the nares and shortening the soft palate. In most Instances, dogs having undergone surgery will be sufficiently and durably improved to never require any additional surgical treatments for their airways. However, a small subset of dogs will deteriorate further with time and require more treatments, especially of their larynx.

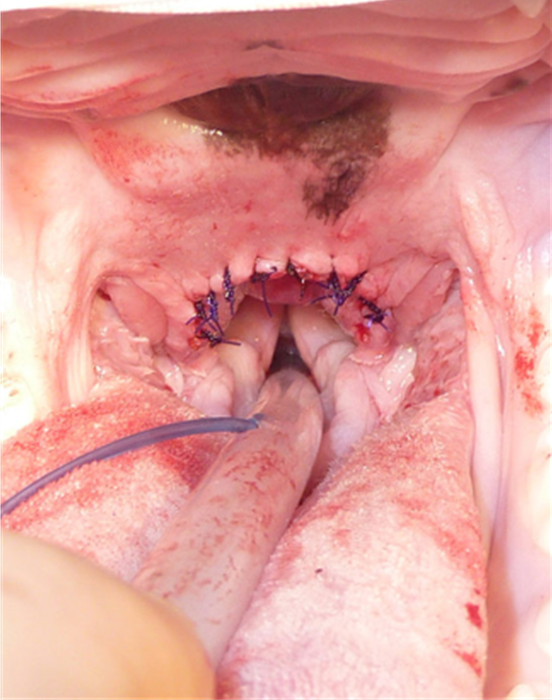

Several techniques are used to address the elongated soft palate. Historically, it was thought that the soft palate of brachycephalic dogs is not only too long but over the last decade, it has been repeatedly shown that it is also excessively thick, obstructing the back of the nose (“nasopharynx”). Classical techniques therefore only aim at trimming the soft palate, removing the excess blocking the entrance of the airways, but leaving the nasopharynx obstructed. Several new techniques have been designed to both shorten and thin the soft palate, improving all aspects of the

obstructions it is causing.

BEFORE SURGERY

AFTER SURGERY

BEFORE SURGERY

AFTER SURGERY

Often, a medical treatment is prescribed for up to a month after surgery, especially in dogs showing digestive troubles before the operation. In most instances, the digestive signs resolve with the treatment and do not recur when the treatment is discontinued, as a result of the overall improvement provided by surgery.

What is the prognosis of Brachycephalic Syndrome?

The prognosis for Brachycephalic Syndrome is good overall. Naturally, it depends on the severity of the disease before surgery, with most severely affected dogs faring worse than less affected dogs.

The time the dog is at the clinic is the most critical. Brachycephalic dogs are high-risk patients and recovery from anesthesia is often delicate. In addition, during the first few days after surgery, the risk of aspiration pneumonia, which can have life-threatening consequences, is higher than usual.

About 95%-98% of dogs are improved by surgery. The worst the symptoms before surgery are the most obvious in their improvement. Virtually all brachycephalic dogs benefit from having their upper airways addressed. Even dogs not obviously affected after surgery require less effort to breathe, which improves their quality of life significantly. Most dogs have better exercise and heat tolerance after surgery compared to before. They also tend to snore less loudly, have less digestive issues and sleep better.

Dr Laurent Findji Senior Clinician, Oncologic & Soft Tissue Surgery / DMV MS DiplECVS MRCVS

Disease Recognition by Owners & Veterinarians Clinical sings that brachycephalic dog owners should recognize...

Respiratory Noise

Dogs with normal upper airway tract breathe quietly. Respiratory noises such as snoring and snorting are indicators of airway obstruction. BOAS affected dogs may present with different types of noise depending on the location of the obstruction: pharynx, larynx, and/or nasal cavity. Some BOAS-affected dogs may only have respiratory noises when they are excited, playing, exercising, eating/drinking or under stress. A thorough veterinary examination is recommended if the respiratory noise is marked.

Pharyngeal Noise

This type of noise, termed 'stertor' is caused by the elongated and thickened soft palate. The caudal tip of a normal length soft palate should barely touch the epiglottis, so that when the dog pants with an open mouth, the airway is open. However, the soft palate in affected dogs is too long and extends into the opening of the airway (larynx). When the dog pants, extra effort is required to move the soft palate out of the larynx in order to allow air to pass. When the dog breathes through its nose, the increased negative pressure within the upper airway tract during inspiration can trigger vibration of the soft palate and soft tissues - BOAS-affected dogs can be 'awake snorers'.

Laryngeal Noise

This type of noise is particularly common in affected pugs. It is called stridor and it is a high-pitched noise, similar to wheezing and different from low-pitched noises like snoring or snorting. Usually this type of noise indicates a narrowed or collapsed larynx. Laryngeal collapse is considered a secondary lesion that may appear as a consequence of leaving primary lesions (e.g., elongated soft palate and narrow nostrils) untreated.

Laryngeal collapse can be temporary and dynamic. During inspiration, the cartilaginous structures are drawn into the tracheal opening. When this phenomenon has happened for an extended period of time, the cartilaginous structures lose rigidity and laryngeal collapse may become permanent.

Nasal / Nasopharyngeal Noise

This type of noise indicates nasal obstruction, usually caused by stenotic nares, abnormal growth of nasal turbinate's (bony or cartilage scrolls in the nose covered by mucosal membranes), and collapse of nasopharynx. In some dogs, a deviated nasal septum may worsen the situation.

The narrowed nasal cavity results in an increase in negative pressure within the airway lumen, which causes soft tissue vibration and noise. This type of noise may be accompanied by nasal flaring, where muscles around the nose contract during nasal breathing. You may also hear a simultaneous, low-pitched and/or high pitched noise. Or it can be a mixed type obstruction, with pharyngeal and nasal noise:

Reverse Sneezing

Reverse sneezing is a common event in brachycephalic dogs, the actual causes of the episode are unknown but it is likely to be related to the elongated soft palate that irritates the throat. Episodes of reverse sneezing usually last from a few seconds to one minute. Usually as soon as it passes, the dog breathes normally again. Reverse sneezing rarely needs treatment. Sometimes, after upper airway surgery, reverse sneezing will stop or decrease in frequency. However, for dogs that have turbinectomy surgery, (some or all the bones are removed) the frequency of episodes might increase until the tissue debris has been cleared out.

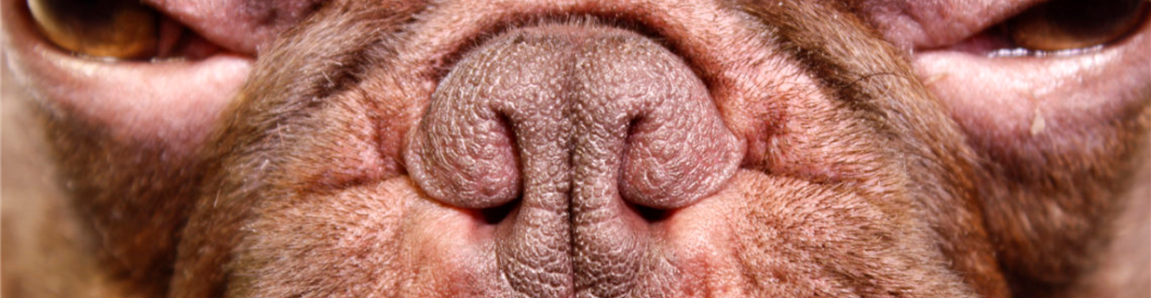

Stenotic Nares (narrowed nostrils)

Stenotic nares are excessively narrow and often collapse inward during inspiration, making it difficult for the dog to breathe through the nose properly. Stenosis has been reported not only in the exterior nostrils, but also in the inner part of the nasal wing (nasal vestibule). As a result, respiratory effort and open-mouth breathing are commonly seen in brachycephalic dogs. Stenotic nares are considered a risk factor for BOAS, particularly in French bulldogs. French bulldogs with moderate-severe stenosis of nostrils are about 20 times more likely to develop BOAS. Widening the nostrils is recommended. The degrees of nostril stenosis in brachycephalic breeds are defined as follows:

Open nostrils - wide opening.

Mild stenosis - Slight narrowing of the nostrils. When the dog is exercising, the nostril wings move dorso-laterally to open on inspiration.

Moderate stenosis - The dorsal part of the nostril wings touch the nasal septum and the nares are only open at the bottom of the nostrils. When the dog is exercising, the nostril wings are not able to move dorso-laterally and there may be nasal flaring (i.e. muscle contraction around the nose trying to enlarge the nostrils).

Severe stenosis - Nostrils are almost closed. The dog may switch to oral breathing from nasal breathing with very gentle exercise or stress.

Gastrointestinal Signs and Eating Difficulties

Eating difficulties are commonly seen in BOAS-affected dogs. The opening of the esophagus is located dorsal to the airway opening and behind the soft palate. In BOAS-affected dogs, the excessive pharyngeal folds and the elongated soft palate may impede the swallowing function.

Regurgitation is commonly seen in BOAS-affected dogs. It can be caused by esophageal diverticula (esophageal pouch es, a congenital condition) and/or hiatal hernia (stomach partially slides into the chest, it may be a congenital or secondary trait). In BOAS-affected dogs, the chronic increase in thoracic airway pressure draws the stomach into the chest, causing gastroesophageal reflux.

Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Sleep-Disordered Breathing

Brachycephalic dogs often have a thickened tongue base, a long and/or thickened soft palate, and hypertrophied nasal turbinate's, which can obstruct the airway during closed-mouth breathing when the dog is sleeping. Eventually, breathing difficulty (dyspnea) and periods of no breathing (apnea) can be observed in these dogs during their sleep. This condition is life-threatening and affects the dog's quality of life.

Heat intolerance

The canine nasal cavity plays a central role in the dog's ability to regulate its temperature. In order to facilitate heat exchange, a dog's nose is filled with an organized network of thin bone structures that are lined with a highly vascularized mucous membrane. These structures form ducts through which air passes, carrying the released heat away from the body when the dog pants. However, this process is hindered in BOAS-affected dogs that have an obstructed nasal cavity. As a result, BOAS-affected dogs cannot exchange heat as easily as healthy dogs when their body temperature rises during exercise. Because they are not able to cool down, they can suffer from heat stroke, which can lead to organ dysfunction. In addition to an increased body temperature (above 39 C), other symptoms to look for include: excessive panting, excessive drooling, dehydration and rapid heart

Cyanosis and collapse

During exercise and sleep, BOAS-affected dogs have great difficulty breathing because of the soft tissue lesions associated with the syndrome. As a result, they may not be able to meet their oxygen requirements. When their blood is inadequately oxygenated, their skin presents a bluish discoloration, which is an obvious sign of cyanosis that can be easily recognized in the dog's tongue and gums. If the dog's oxygen levels are not stabilized immediately, he/she may collapse or become unconscious.

Information provided by: webmaster@vet.cam.ac.uk

What is the treatment for brachycephalic airway syndrome?

Since obesity worsens the signs of brachycephalic airway syndrome, weight loss is an important part of treatment if your dog is overweight. For dogs with only mild or intermittent signs their condition may be managed conservatively by controlling exercise levels, avoiding hot or humid conditions, keeping the dog in an air-conditioned area during the summer, and avoiding unnecessary stress.

Corticosteroids, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and oxygen therapy may all be useful for short term relief of airway inflammation or respiratory distress. However, medical management of this condition does not correct the underlying anatomical abnormalities.

Surgery is the treatment of choice whenever it interferes with the pet’s breathing. Stenotic nares can be surgically corrected by removing a wedge of tissue from the nostrils, allowing improved airflow through the nostrils. An elongated soft palate can be surgically shortened to a more normal length. Everted laryngeal saccules can be surgically removed to eliminate the obstruction in the larynx.

How successful is surgery?

The earlier that the abnormalities associated with this syndrome are corrected, the better the outcome. The condition worsens over time and may cause other abnormalities. Early correction of stenotic nares and/or an elongated soft pal ate will significantly improve airway function and may prevent development of everted laryngeal saccules. In the early post-operative period, swelling of the surgical sites may occur and interfere with breathing. Therefore, your veterinarian will monitor your pet after the surgery has been performed.

Extra advice

Dogs with brachycephalic airway syndrome should be fitted with a harness that does not tug at the neck area. It is not advisable to use a regular neck collar for these dogs, since the collar can put undue pressure on the neck. This syndrome is directly related to the conformation or breed standard for brachycephalic dogs. Dogs with pronounced breathing difficulty or dogs that require surgery to correct airway obstruction should not be used for breeding. It is usually recommended that these dogs be spayed or neutered at the same time that the surgical correction is per formed.

Contributors: Krista Williams, BSc, DVM; Cheryl Yuill, DVM, MSc, CVH